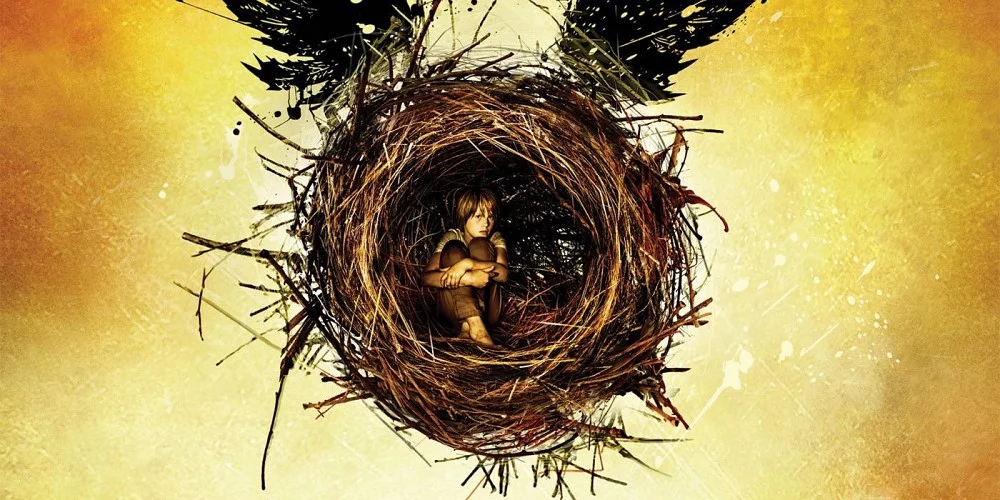

Off the Shelf: Harry Potter and the Cursed Child

Off the Shelf is when we talk about books we've read lately. A book is a really antiquated thing that people pretend to like when they want to sound smart, which fits the goal of this website quite nicely.

Let’s be adults about this: Harry Potter and the Cursed Child, as a script, is not good. It’s the epitome of contrivance and elbow-nudging see-what-we-did-there fan service. Some things are held up in syrupy “remember how great this was?” reverence, and other things are bafflingly ignored or neglected. It’s a downer to read, but not too much of a downer, because by nature of being attached to the Harry Potter brand at-large, it’s paradoxically inconsequential. The interesting thing here is not the question of quality; what’s interesting here is why Cursed Child’s lack of quality probably doesn’t matter, despite the indignity surrounding its existence.

When cultural touchstones reach a degree of prevalence that goes beyond persistence and enters immortality (think of the difference between something like Divergent and something like The Hunger Games—both are huge successes, but they’re still popular in different ways and to different degrees), the immortality comes with a special privilege, and that privilege is immutability. Things that are “merely” cultural smashes can still be marred by crummy brand extensions—the Divergent movies sort of stink, and that reception muddies the overall impression of the series—but things that are culturally immortal can escape subpar interpretations, continuations and reboots. Like Michael Jordan’s stint with the Washington Wizards, we’ve all decided that things like Mockingjay: Part I or Midnight Sun (this was the Twilight spin-off from Edward’s POV—shoutout my Lord and Savior Jesus Christ for keeping this one away from publication) are at worst regrettable and at best forgivable. When things are great without precedent, it’s okay when they mess up.

So if Cursed Child is panned off-stage, does it matter? Probably not. Try as the marketers might, it’s obvious that J.K. Rowling was pretty distal from the creative process, perhaps entirely removed from the writing process, and overall probably saw this as something that would pay homage before it became canon. It’s a novel accessory. A widget. Even if the jacket says this is “the eighth story,” it’s not that, and it won’t be seen that way.

The sting of reading this play, then, doesn’t come from its utter averageness, but instead its rather appalling overconfidence. The whole thing is awash in a “we’re giving the people what they want!” vibe, but it feels so miscalculated because this is precisely what we didn’t want.

But—you might argue—people wanted more Harry Potter! Yes, but in a very particular sense. I don’t think anyone finished Deathly Hallows and held out hope for another book—the ending of the seventh novel, coupled with its gentle-but-firm epilogue, is conclusive and permanent. By jumping ahead in time, Rowling effectively covered the temporal distance in between the last chapter and the epilogue with a giant “I know what happens here, but it’s not important enough to write about” label, and we all accepted that and took the conclusion and held onto it as a success. There were no loose ends, and the few unanswered questions that remained (like what the characters do for a living) were so inconsequential that their lack of attention was perfectly acceptable. The world of Harry Potter was boundless and dynamic and deep, but it was also tightly sealed, like a snow-globe you could pick up over and over, but never could—or even wanted to—change.

We all wanted more Harry Potter because we wanted to recapture the feeling of diving into something that was joyous, sensational, sweeping, and universal. Modern pop culture hasn’t seen the same unification around one property since, and it might not ever again. When we say we wanted more Harry Potter, we weren’t talking about a sequel, we were talking about an experience. And it’s Cursed Child’s failure to make that distinction that makes it feel like a failure. It announces itself as the story we’ve all been waiting for, but who was waiting in the first place? Reading a Harry Potter book was about more than what happens next, it was about immersion into an astounding world that toed the line between imagination and reality with uncanny dexterity. “More Harry Potter” was about going back into that world—whether it was sitting in a movie theater at midnight or riding a roller coaster—and Cursed Child doesn’t grasp that at all. Hogwarts, and the wizarding world it occupies, feel far away in this new story. It’s kind of sad.

On the cusp of a cultural moment with more “more Harry Potter” than ever—the inevitable expansion of this performance and the incoming Fantastic Beasts movie (movies?)—it’s hard to find solid footing. On the one hand, we could fall back into the safe, cozy magic of the books that started this whole grand adventure, but on the other, we could totter forward—gracefully? perilously? blindly?—into a time when Harry Potter means more than seven years at Hogwarts. Other properties are out in front—Marvel, DC, Star Wars, even Game of Thrones to a degree—and there’s encouraging precedent to believe that it’s possible for titles to expand past their original medium. But when the worlds and characters we love draw closer to home, they somehow run the risk of growing more distal.

Hogwarts always balanced itself perfectly. It was a home, but it was always just out of sight, around the corner, on the next page. It’s a scary thought to imagine walking inside, entering the Great Hall, looking up at the ceiling, seeing the stars, and then realizing that they were just painted on. Like a set on a stage.