Serial

The rise of podcasts.

An inherent contradiction lies at the heart of listening to a podcast. Like most tech-related things of the decade, podcasts are isolating and solitary. You put on your headphones and tune in and block everything else out. At the same time, podcasts create a sense of intimacy. It’s just you, the host, maybe a guest or two, and some intelligent, funny, or engaging conversation. Podcasts are another way the internet promotes personal culture, but perhaps among everything related to smartphones, they do more than most apps to make us feel connected with other people.

Podcasts—an invented word derived from iPod and broadcast—betray their simplicity as soon as you have to describe them to the uninitiated: They’re radio shows you can stream to your phone. Many long-running, popular podcasts represent this definition well. The Joe Rogan Experience has a shock-jock quality to it thanks to its weed-smoking, unfiltered, maybe-possibly-almost-definitely problematic host, while The Ben Shapiro Show channels the tenants of conservative talk radio into a podcast that would be right at home on your AM dial[1]. WTF with Marc Maron, an interview show from a B-list comedian featuring A-list celebrities, lands somewhere between shock-jock ravings and talk-show ramblings, although its length and propensity for tangents give it a breeziness that’s more welcome in an on-demand format than traditional broadcasting (of which Maron is a veteran)[2]. Of course, the world of podcasts contains plenty of radio imports, too. Look no further than NPR staples like Fresh Air, Wait Wait Don’t Tell Me, and Pop Culture Happy Hour for evidence that even classic radio shows can translate to your phone.

Yet as podcasts have grown, more shows have taken advantage of the medium’s portability, instantaneousness, and temporal freedom to legitimately innovate within the form, and thus you have numerous podcasts that couldn’t exist as radio shows. Jon Mooallem’s Walking podcast, for example, is just the ambient sound of the host hiking through the woods, while Slow Radio collects sounds from all over the world and arranges them into audio tableaus (“Armistic Sonic Memorials,” for example, collects sounds from wars throughout history, from the Somme to Afghanistan to Vietnam).

Other podcasts make subtle tweaks to radio stylings that, while less gimmicky or brow-raising than Walking or Slow Radio, do more to expand what a podcast can be. It is here, finally, where we arrive at Serial, not just the most popular podcast of all time, but the most influential, too. Serial is how podcasting went from a mere convenience—you can take the radio anywhere—to a creatively boundless arm of popular culture.

Serial is an offshoot of This American Life, and it’s representative of that program’s deviations from classic radio. From when it began in the late 1990s to throughout the 2000s, This American Life was the closest thing radio had to high-production storytelling. It found an idealistic, somewhat romantic host/producer in Ira Glass, incorporated a richer array of sound than was normal on radio, and delivered its prescient, thoughtful, probing stories with a delicate tone that somehow relaxed NPR’s stiff, highbrow posture into something that sounded more like an interesting dinner guest than a pretentious lecturer. This American Life was a huge leap forward for radio, and its innovative approach to audio narrative would make way for Serial’s titular structure.

Despite Serial’s initial subject matter, its title refers to the way it tells its story rather than a brand of killer. When the show was conceived by producers Sarah Koenig (who would also host) and Julie Snyder, the “what if” that drove its creation wasn’t “what if we followed a cold case to see if we found anything new,” but rather, “what if we told a story on the radio episodically (serially), in which each segment built upon the last.”

It’s a concept that could only be executed in the world of podcasts. How would This American Life, to use the most direct alternative, have programmed something like Serial? They couldn’t have done so on radio, where they’d have to ask listeners to tune in at the same time every day, for the same amount of time, without the myriad interruptions and distractions that come with driving your car. Serial could have only been a podcast, but it was the content itself that brought it widespread attention to match its innovations.

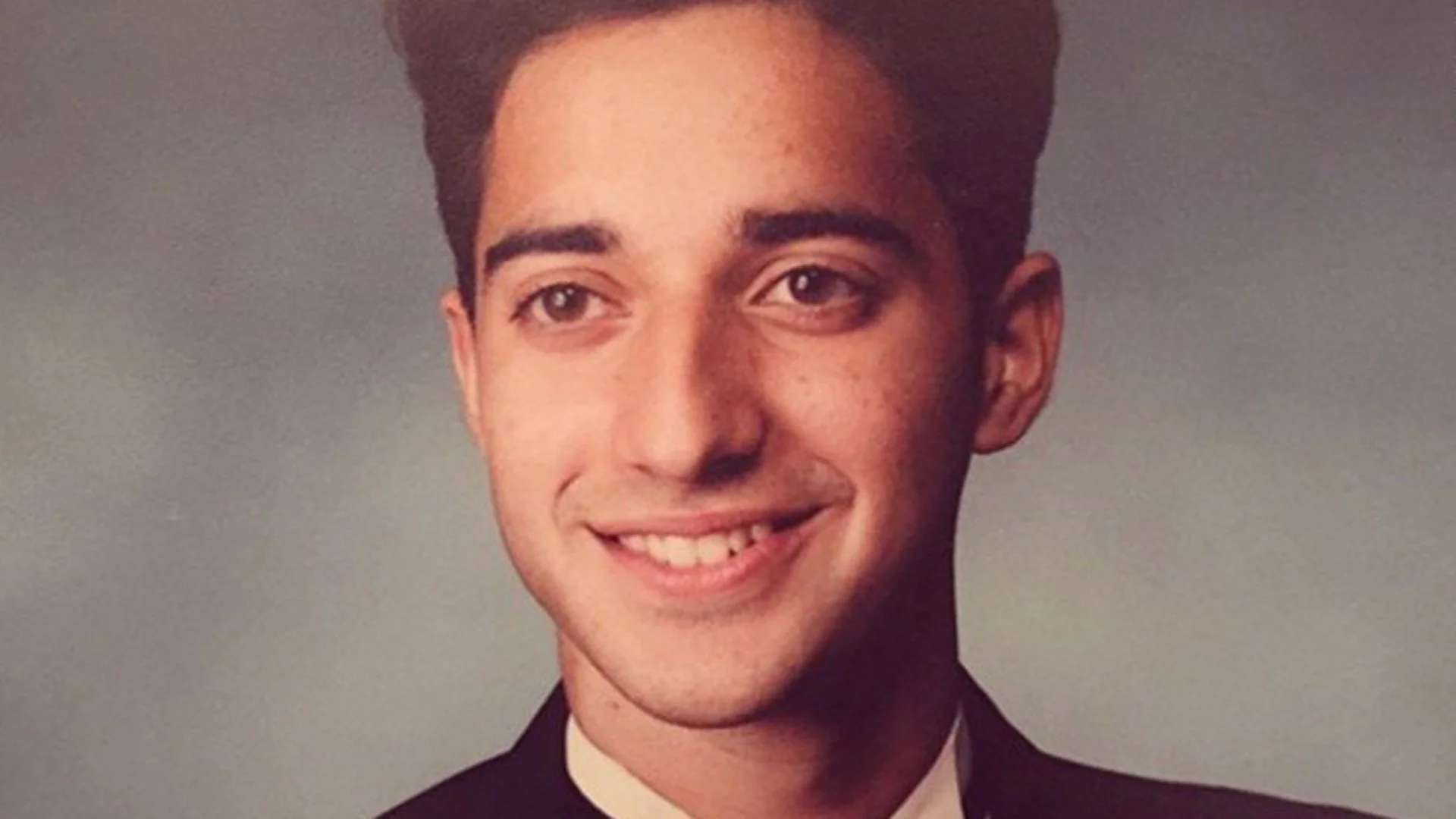

Serial follows Koenig[3] as she investigates the 1999 murder case of Hae Min Lee, an 18-year-old Baltimore high school student found dead in a park in Baltimore County[4]. Three days after Lee’s body was discovered in 1999, an anonymous source suggested authorities investigate Adnan Syed, Lee’s ex-boyfriend. Syed was arrested two weeks later and charged with first-degree murder. Despite maintaining his innocence, a six-week trial resulted in Syed being found guilty of Lee’s murder. He was given a life sentence in prison.

Over the course of 12 episodes, Serial reopened Syed’s case to see if he had been wrongfully convicted. The investigation unfolded in near-real time—Koenig and Snyder and the rest of the crew began the podcast before their reporting was finished—and covered everything from previously debunked leads to leads that had gone dormant to alibis that seemed questionable to testimonies that felt inconsistent. On top of the case itself, Serial painted a rich picture of its characters, offering a sensitive profile of Lee, introducing friends and acquaintances who could speak on the parties involved, and—crucially—conducting extensive interviews with Syed himself.

And although Syed maintained his innocence throughout Serial, part of the program’s intrigue became Koenig’s conflicting opinions, theories, and impressions of the accused. In multiple monologues, Koenig wrestled aloud with her doubts and convictions about the case, at times voicing trust in Syed, other times intense skepticism. It was a critical hook within a murky investigation. As Serial swam through the cloudy details of the case, struggling to piece together accounts that didn’t line up, the listener felt their allegiances to the suspects waxing and waning along with Koenig’s.

It’s one of the earliest examples of the intimacy podcasts can create between audience members and producers. You tuned in to Serial to hear about the case; you stayed because Koenig reflected all your points of obsession.

However, in its heyday, Serial managed to not just find universality in its story, but leverage that into creating a full-blown community around the show. Some of the most popular podcasts today have collectives of fans—Marc Maron calls his listeners “What the Fuckheads” and My Favorite Murder, a true-crime podcast (that owes its success in part to Serial) has legions of “murderinos”—but these are outliers in how they place individual listeners within a greater whole. In most cases, the average podcast listener doesn’t feel more than a one-to-one relationship between themselves and the host. Serial, meanwhile, launched a hive of investigators. People who followed the show week-to-week started to dive deeper into the leads, alibis, and accounts Koenig and Co. presented. It was like the Lost phenomenon on TV in the mid-aughts, but with real stakes.

It was an unforeseen advantage of Serial’s lack of a predetermined conclusion. Reddit users organized search parties and meetups, thousands of people wrote into the show to share theories and suggest follow-ups, and the most passionate listeners actually flew to Baltimore to revisit the crime scene or track clues on their own. Serial expanded beyond its weekly episodes. It entered the news cycle. It caught the internet’s content wave at its peak.

Something about Syed’s case and the crime against Hae Min Lee captured people’s fascinations. Koenig has said Serial’s appeal lay in its classical narrative touchpoints—“It’s about the basics: love and death and justice and truth,” she once said—and while that broad diagnosis feels true, it doesn’t feel complete. Serial wasn’t popular because it embodied a generic concoction of human storytelling. It was popular because it touched a primal nerve.

In the past decade, true crime has become a sprawling and uber-diverse genre in a way it wasn’t even in the days of In Cold Blood or the O.J. trial. Solely in the world of podcasts, Serial’s cold-case investigation spawned a subgenre. Up and Vanished, Searching for Richard Simmons, Jensen and Holes: The Murder Squad[5], Bear Brook, and 22 Hours: An American Nightmare all followed (or follow, continuously) unsolved or unsatisfying past cases with the desire to uncover the truth (or, at the least, snatch up a Casper sponsorship[6]). As discussed previously, armfuls of other podcasts are devoted to gabbing about true crime in general, from My Favorite Murder to Sword and Scale to shows that dive deep into a single case or a related series of cases, like Man In the Window, To Live and Die In L.A. and Monster: The Zodiac Killer.

True crime exploded on TV in the 2010s, too. Making a Murderer became one of Netflix’s biggest original hits ever in 2015; like Serial, it followed a judicially shaky murder case and revisited its evidence[7]. Netflix had additional true-crime hits with The Staircase, The Keepers, and Confessions with a Killer: The Ted Bundy Tapes. Meanwhile, HBO’s crime bona fides were established with 2015’s stunning miniseries The Jinx, and Hulu found awards recognition with its dramatized account of The Act. Amazon lacked in the originals department, but was quick to scoop up classics like Ken Burns: The Central Park Five and Dear Zachary. Serial launched a cross-platform arms race in the genre, and television was perhaps the largest battleground.

These inventories don’t account for all the historical fiction or, better still, the satire that’s resulted from the true-crime explosion, either. Netflix’s Mindhunter is the most popular of the bunch—it’s a dramatized account of the FBI’s early classification of the “serial killer” concept[8]—but you could stretch the genre to include shows like American Crime Story[9], Top of the Lake, Broadchurch, or a series featured in this collection: True Detective. The saturation of dour, self-serious dramas sparked an inspired comedic response. A couple comedy podcasts sent up Serial itself—Done Disappeared and The Onion’s A Very Fatal Murder were the best—but few things upended, picked apart, and exposed the clichés of Serial, Making a Murderer, and The Jinx better than Netflix’s half-hour comedy American Vandal, a mockumentary series that investigated high school pranks as if they were heinous crimes[10].

While Serial’s fleet of rip-offs and spin-offs doubtless contained myriad surprises, one of the more unanticipated cultural trends within the true crime explosion was the genre’s intense support from women. Not only did women embrace true crime more than men, the data shows the difference is almost shockingly lop-sided. In 2010, it was reported 70 percent of Amazon reviews for true crime books are written by women[11], and while most true-crime shows have audiences that skew female, popular crime talk shows like My Favorite Murder and All Killa No Filla boast female listenership as high as 80 percent.

The reasons for this are varied, complex, and certainly beyond the authority of a straight white culture writer, but several experts on the subject have reluctantly boiled down the phenomenon to a few factors:

Empathy. In case you haven’t noticed, it’s not very safe for women in the world, and the number-one threat to women, unfortunately, are dangerous men. This is why women go out in pairs and keep an eye on each other’s drinks and carry mace. No matter if a woman is especially brave or strong or watchful, everyday life presents risks to her that a man doesn’t have to worry about, and this means women sometimes have unique anxieties that can’t be processed with or understood by men simply because men don’t share them. The result? A need for female-centric spaces where those anxieties can be processed. True-crime podcasts are one such space.

Writer Rachel Monroe, author of the book Savage Appetites, which covers the intersection of true crime and modern womanhood, acknowledges this formulation but also gives a warning against it: The appeal here isn’t just empathic victimhood.

“There’s a discomfort with women who are interested in creepy things or having proximity to death or violence,” Monroe said in an interview with Jezebel. “The one storyline [about female fervor for true crime]—that it’s for the victims or it’s to avoid being a victim—is trotted out a lot. It allows us to maintain [popular culture’s] sense of virtuous womanhood while explaining this draw of violence.”

Empowerment. At the same time, Monroe explained there’s a reverse side to the victim angle. By processing stories about female victimhood, women can claim ownership over these stories instead of having to be defined by what other demographics, influencers, or thought leaders say about them: “Broadly speaking, people who have been raised or socialized as female absorb a ton of messages about our own vulnerability. There is a cultural fascination with wounded women and I think taking that back and owning that obsession can be a way to control or rewrite something you find troubling.”

Monroe puts it more succinctly later in the interview. This answer carries particular resonance within the world of podcasts: “Part of the appeal of the trope of the dead white woman is she can’t speak for herself, so other people can speak for her.”

Kinship. True crime podcasts, particularly more—for lack of a better word—casual shows like My Favorite Murder, make it alright to be fascinated with violent, dark, evil stories. Contrast Serial with the macho broodings of True Detective. For all of True Detective’s stimulating philosophical tangents and stylish depictions of damaged individuals, it’s a super male show. We’ve seen this watch-the-world-burn stuff before, be it Taxi Driver or Fight Club or, yeah, The Dark Knight. Those movies aren’t dude-specific, but they land as dude-specific, and the reverse goes for My Favorite Murder or Serial or anything that captures a female-dominant audience. Are these female-centric shows? Not necessarily; they’re not really about “women’s issues” (although, murder is a woman’s issue, to put it in odd terms). But they resonate with women in part because their basic constructs give women permission to express their interests with other women.

Karen Kilgariff, co-host of My Favorite Murder, told Rolling Stone: “I want to know the things people won’t talk about. I want to talk about the things that people don’t think you’re allowed to talk about. I remember seeing a map of where the bodies were buried in [John Wayne Gacy’s] house, having crazy chills, and then turning the page like, ‘Can I read how those bodies got into that house?’”

Georgia Harstack, her co-host, agreed their show’s sensitivity to victims and affirmation of true-crime obsessions has created a unique environment for their listeners: “It’s hard to toe the line between warning people, especially women, to be aware of their surroundings and victim-blaming,” she said. “Like, ‘Why did you walk down an alley by yourself?’ That’s not the reason she got murdered. The reason is that there was a fucking murderer there.”

At its best, the true crime genre gives people an outlet to process their fears, information to combat their anxieties, and a community that affirms they’re not a psychopath for going down an internet rabbit hole about the Golden State Killer. At its worst, it romanticizes killers and revels in the grotesque (the satire podcasts make particular note of this).

Serial succeeded and persists because—critically—it established great true-crime not as sensational but as grounded and revealing. Hae Min Lee is kept at the center of the story, sometimes forcibly, and while Koenig wrestles back and forth with her feelings about Syed, expressing sympathy and compassion for him as much as she casts doubt and disturbance over his account, the accused is kept at a cautious distance. He has his say, but Koenig and Snyder and the rest of the crew don’t hand the keys over to him. It’s well done. Few true crime shows do it better.

The first two seasons of Serial (the second season follows a different case, about a U.S. soldier captured by the Taliban[12]) have been downloaded over 340 million times. The show’s had incredible legs, but its rise was historic, too. When Serial launched in October 2014, it reached 5 million downloads in just a month (the fastest podcast ever to the benchmark), and by December, it had 40 million downloads. In a medium where a show’s popularity is still largely determined by word of mouth and internet thinkpieces, it’s a remarkable spread[13].

Podcasts, of course, wouldn’t be the same after Serial’s success. The numbers today are mind-boggling: There are over 700,000 estimated podcasts to sample, 28 million individual episodes, $660 million in advertising revenue by 2020, and an estimated $1.6 billion in advertising revenue by 2022. Half of Americans have listened to a podcast (the huge majority between ages 18-54), and the typical podcast listener averages seven separate shows per week. Seventy-seven percent of podcast listeners listen to more than seven hours of content per week, too.

Amid a landscape of what many deride to be mindless video games, dumb Hollywood blockbusters and way, way too much TV, the ubiquity of podcasts can be seen as a blessing, almost a pseudo-elitist counter to the sludge of popular culture[14]. In fairness, the best podcasts are intellectual exercises. Malcolm Gladwell’s Revisionist History examines possible glitches in modern institutions and structures, Forever Dog’s Black Men Can’t Jump In Hollywood explores the intersection of race and filmmaking, The New York Times’ The Daily somehow presents a 30-minute well-reported story every weekday, and NPR’s How I Built This pairs crack interviewer Guy Raz with a different entrepreneur each episode to discuss the origins of their success. Podcasts are indeed worldview-stretching.

At the same time, podcasts are bubbles. As much as some shows garner legions of fans, the act of listening to a podcast is lonesome and solitary. Podcasts are for headphones, workouts, and commutes. They’re only interactive in the sense that you think along to them in your own head. The community of podcast listening is a bit arbitrary, and the prospect of sharing a podcast with another person is close to that of sharing a television show: They’re something you “add to your list” and probably never, ever actually follow up about.

So while Serial popularized and legitimized a new storytelling medium in the 2010s, it also popularized and legitimized a new way for people to plug in and tune out. If anything, podcasts are a more forgivable way to plug in than anything else in pop culture. Since you’re not staring at a screen or typing at a keyboard, it appears to proffer the possibility of outside engagement, but that’s not really the case. Podcasts kidnap your attention as much as anything else on your phone, and they disengage you from the present as much as anything you have to watch or play. The attention economy is as prevalent on Luminary, Stitcher, Apple Podcasts, and Soundcloud as it is on Netflix, Hulu, Steam, or YouTube.

Going forward, the greater accessibility of podcasts could see the bubble swell even larger than it already has. Professional production thresholds—high-quality microphones, sound-proof studio space, versatile mixers—might drop away akin to what’s happened in photography or filmmaking. In a world where an iPhone can make you a YouTube star, a professional photographer, or a spontaneous broadcaster, it’s just as likely to make it possible for you to become a shock jock radio host, breaking-news journalist, or—when considering something like Serial—investigative reporter. Serial proves the professionals still deliver results impossible to match, but it gives no indication that you couldn’t try to solve your own mystery anyway. Have you seen your neighbor lately? Might be worth a look. Don’t forget your phone.

[1] Curiously, podcasts are the one venue in popular culture where conservative dialogue seems to be as accessible as liberal dialogue. As popular as leftist podcasts are, for every Crooked Media (Pod Save America) there’s a Daily Wire, which puts out Ben Shapiro’s show alongside an armful of other hard-right commentators. Even non-political genres like sports have right-sided representation through companies like Barstool, which has garnered fervent support for its conservatism. Of course, Barstool is also known for being sexist and disgusting, but they remain a good case study of how podcasts, despite the youth of their consumers, exist in a bipartisan landscape.

[2] Though this reputation has been lost amid the rising ubiquity of confessional, interview-centric podcasts, Maron’s show was once known as the place where guests went to cry. Maron’s approach to each conversation was straight-forward, but disarming. As soon as a guest hinted at “a rebellious phase” or “a difficult time,” you could count on Maron to interject with something like “what, drugs?” or “you get along with your parents?” to pull wild memories from his subjects. The guy might be schluppy, but Maron is sensitive and unpretentious (probably in part due to his own history with addiction and abuse). He’s a master.

[3] You might call Koenig the David Simon of podcasting. Like Simon, she was a crime reporter in Baltimore (they were both at The Baltimore Sun, in fact) before she made a jump to another form of media (in her case, radio, and in his case, television with Homicide: Life on the Street and The Wire).

[4] Coincidentally, Hae Min Lee lived about a block from Ira Glass’ childhood home.

[5] Maybe the worst name for a detective duo of all time.

[6] A quick list of companies who apparently sponsor every podcast ever made: Casper, Squarespace, Blue Apron, Hello Fresh, Audible, ZipRecruiter, MailChimp, LegalZoom, Rx Bar, Wix, Stamps.com, and motherfuckin’ SimpliSafe, because I guess something as important as home security needs to have a cute little name and a trendy misspelling to be accessible to tech-savvy millennials.

[7] While Making a Murderer’s investigation of Stephen Avery’s conviction was gripping, it was revealed not long after its release there was a good deal of evidence the documentary conveniently omitted from its final cut. The full breadth of facts makes Avery seem a lot guiltier than the show would have you believe.

[8] Mindhunter has some prestige trappings thanks to the involvement of acclaimed director David Fincher, but it’s the closest thing pop culture has to a “Forrest Gump with serial killers” show, with the two lead detectives bumping into everyone from Charlie Manson to David Berkowitz to John Wayne Gacy. The scenes in which the detectives interview the killers are riveting, but it’s a bit kitschy in execution, like a murder-themed amusement park.

[9] American Crime Story’s first season, The People v. O.J. Simpson, is on the shortlist of best seasons of TV this decade. The second season, The Assassination of Gianni Versace, was fine, but lacked the prescience, electricity, and relevance of the O.J. account. It was a great decade for O.J. examinations overall. ESPN’s six-part documentary O.J.: Made In America, part of its 30 for 30 series, won the Academy Award in 2016 for Best Documentary Film.

[10] Pages could be written about the unexpected brilliance of Vandal, but for now, we’ll just give a teaser: The first season follows a wrongful conviction case in which a class clown is accused of spray-painting penises on every car in his school’s faculty parking lot, and the second season follows a case known as “The Brownout,” in which someone puts a high-powered laxative in the cafeteria lemonade at an elite private school. There is no hesitation in the following sentence: American Vandal is a genius show.

[11] This isn’t a “women are more likely to write reviews” number, either. For comparison, the same study found books in Amazon’s “war” category are reviewed by men 82 percent of the time.

[12] The third season, released in 2019, covers the mechanics of the criminal justice system in Cleveland.

[13] No great revelation here, but it’s an interesting point of speculation to wonder how far podcasts can go under their current publicity model. That is to say, few podcasts are advertised outside the world of podcasts, so as we enter the 2020s, it will be interesting to see when total listenership plateaus across the medium. That figure could point to a lot of other things, such as how most people use or don’t use their smartphones, how effective digital-only advertising can take something, or what the barriers are that stop some smartphone users from opening an app that’s already on their phone and taking advantage of it.

[14] But again, remember the bipartisanship we footnoted earlier: As much as their tie to smartphones and their intellectual underpinnings would make podcasts seem like something confined to the bubble of the “arrogant liberal elite,” the numbers don’t bear that out. There is a podcast for everyone, and young people of all belief systems, political leanings, and identities have popular, mainstream shows they frequent.