Serious Question: Which Rap Song Makes You Most Afraid For Your Life?

One of the most popular rap songs of all time is 50 Cent’s “In Da Club.” It’s a terrific song—the production bangs, 50 Cent’s lyrics are fun and funny (he somehow crams allusions to smoking weed with Xzibit, cracking a bottle over some guy’s head, and a three-way sexual encounter all into one song), and there’s even tiny moments where Eminem chimes in with little “Uh-huhs” and “I’m aights.” It’s a perfect party song.

But there’s a problem with that. See, while “In Da Club” is a perfect party song, 50 Cent is far from a perfect party rapper. In fact, many would point out that “In Da Club” directly contradicts the street-hardened gangster persona that 50 Cent had previously established for himself. Think about it: In the same song, 50 talks about recovering from his bullet wounds (“been hit with a few shells but I don’t walk with a limp”) and the details of his personal romantic policy (“I’m into having sex, I ain’t into making love”). It’s almost like a plot hole. Why’s 50 in da club, anyway? By being in the club, is he distracted from more important things happening out on the streets? Shouldn’t he be there instead? These are weird questions, but if you poke at “In Da Club” long enough, there’s reason to ask them.

This is the “In Da Club” paradox, and it’s not uncommon. In fact, “In Da Club” is just one example of a broader trend in hip hop: The legitimacy of rap is fluid. When 50 started partying like it’s your birthday, we stopped taking him seriously as a “legitimate gangster.” Songs like “What Up Gangsta,” where he raps: “Front on me, I’ll cut you, gun-butt you or buck you” don’t really have the same impact anymore. Despite 50’s undeniable history of violence, his threats after “In Da Club” no longer feel that life-threatening. That’s interesting.

Going forward, we’re going to look at how various hip hop artists leveraged life-threatening language. What did they say? How did they say it? What was the reaction from the public (some threats are funny; some are scary)? Was the threat legitimate, or was it weak sauce? How did violent lyrics affect the perception of that artist? These are all smaller Serious Questions within the big-time Serious Question. Let’s go.

***

Can any emcee be life-threatening? No. While some rappers are board-up-your-windows terrifying in their words against your life, others definitely are manageable in a direct physical encounter. We’re not going to explore these rappers in depth, but since they’re easy to make fun of, we’ll list a few for mockery’s sake:

Rappers Who Can Never Be Life-Threatening:

- Ludacris—On his 2004 album Red Light District (yikes), Ludacris has a song called “Get Back,” where he says: “On my waist there’s more Heat than a Shaq Attack/But I ain’t speaking about ballin/Just thinking about brawlin till y’all start bawlin.” When Ludacris says he’s going to make me cry, I picture the two of us watching a sad romance movie together. When DMX says he’s going to make me cry, I picture him burning my house down. See the difference?

- Drake—Guess what Drake has in common with Charmin? They’re both super soft and belong in a toilet. Boom, roasted.

- J. Cole—He has earnest, sincere songs about wet dreams and masturbating. Like, I know Christian rappers harder than J. Cole.

- Chance the Rapper—Sorry, it’s true, but there’s a silver lining: Chance has a pass here because he doesn’t attempt to position himself as a threat within the wider world of hip hop. That’s key to this discussion. You don’t stink at a game until you play it.

- Kid Cudi—Rappers can cry and still be threatening, but Kid Cudi is like the rap version of the “Leave Britney Alone” girl, you know?

- Iggy Azalea—If someone approached you and said, “Hey, we need you to pick one rap artist to help you blow this $1000 Visa gift card on clothes,” the correct answer is Iggy Azalea. Unfortunately, that means she will never threaten your life in a meaningful way. (Second on the roster for this scenario is Childish Gambino, but he still has potential to be life-threatening because after Awaken, My Love! it seems like he can do anything, including murder.)

So already a pattern is emerging. For a rapper and their song to feel scary and substantial, said rapper needs a little something extra. Real anger, real emotion. Namely, a purpose. Like any great bad guy, rappers laying down evil promises need backstory and context. Without that, they aren’t much more than Ludacris picking a fight, and who wouldn’t pick a fight with Ludacris? I mean, I can picture my grandmother smacking Ludacris around. What does he come back with? Nothing, man.

However, there are still plenty of rappers who my grandmother should super super not smack around. That’s why we’re here. That’s what we’ll talk about now.

Which Rap Song Makes You Most Afraid For Your Life?

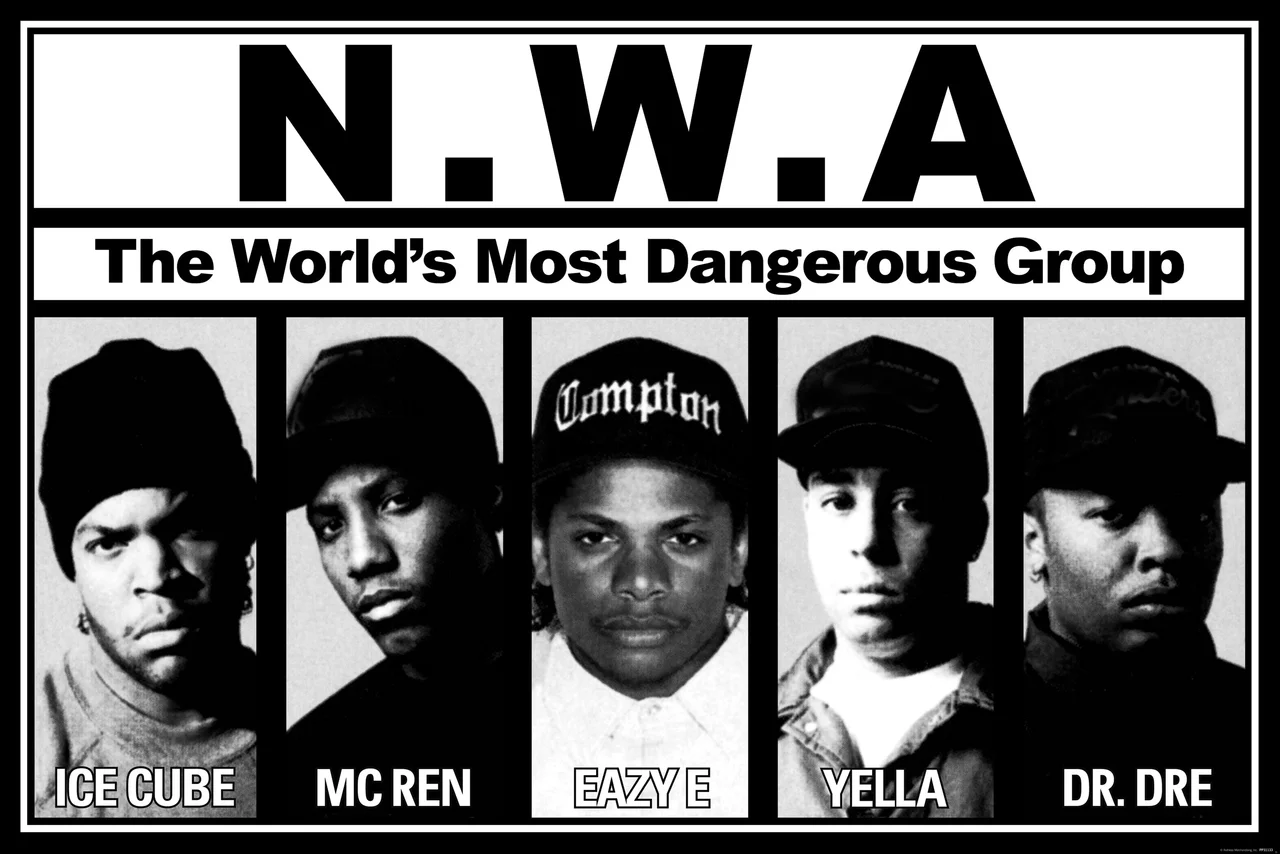

“Straight Outta Compton” by N.W.A.

The Threat: Ice Cube yells, “When I’m called off, I got a sawed-off/Squeeze the trigger and bodies are hauled off”

You Should Fear For Your Life If: you currently hold or are considering a career in law enforcement; you are taking NWA too lightly

Purpose of the Threat: strengthening the collective image of NWA as hardcore and merciless

Truth be told, literally any lyric in “Straight Outta Compton” can be chosen as the marquee threat, because all of this song is an uncompromising, unedited, unadulterated takedown. Eazy E says he’ll suffocate your mother with a pillow. Ice Cube brags that his crime record rivals that of Charles Manson. MC Ren tells you he’s already looking at you through the scope of his rifle. There’s a reason this is one of the most important rap songs ever: The directness of “Straight Outta Compton” made listeners feel like NWA was talking to them personally—they’re coming for your family, your neighborhood, your life. The song was dangerous in its content, but to many it was also dangerous in its confidence and authority. The threats are too intense to be denied; they turn NWA into a collection of supervillains.

Though this was the opening track on their major-label debut, NWA’s position on “Straight Outta Compton” is high and mighty. Others look up straight into their gun barrels. And if you dare challenge their rule, the response to the criticism is built into the song: Want to dismiss these guys as thugs or fools? No problem. They’ll kill you.

“M.E.T.H.O.D. Man” by Wu Tang Clan

The Threat: Method Man says, “I’ll fuckin—I’ll fuckin sew your asshole closed, and keep feedin you and feedin you and feedin you and feedin you”

You Should Fear For Your Life If: You like hassle-free bowel movements; you have lots of dietary restrictions; you are anyone, anywhere, at any time

Purpose of the Threat: unify the members of the Wu Tang Clan under a common banner

We’re not messing around here, okay? Method Man drops this threat in a precluding skit to his solo song on Wu Tang’s 1993 album, Enter the Wu Tang. People who follow hip hop closely know this moment as “the torture skit,” when Method Man and fellow Wu Tang-member Raekwon take turns talking about how they would torture someone. Other things that come up: hitting someone in the nuts with a spiked baseball bat, sticking a hot coat hanger up someone’s rectum, and stabbing someone in the tongue with a rusty screwdriver. It’s appalling. It seems impossible to desensitize yourself to it. It’s one of the most explicit moments in the history of rap.

It’s also sort of funny. If you listen to the skit, you’ll hear the other members of the Wu Tang Clan laughing and guffawing in the background as Method Man and Raekwon raise the stakes higher and higher, until Method Man closes out with the lines above. The background noise of the Clan all together functions almost in opposition to the back-my-homies-up dynamic of NWA. It’s not an aggressive, “accept us…or else” kind of collectivity; it’s a “take us or leave us” kind of vibe. Method Man’s torture fantasy is disgusting, but the response from the group makes it feel fun. It makes you like Wu Tang a little more. Of course, on the other hand, the rest of the album is as life-threatening as they come (the very first line is Ghostface Killah screaming: “Ghostface! Catch the blast of a hype verse/My glock bursts, leave in a hearse, I did worse!”).

Maybe Method Man was serious after all.

“No Vaseline” by Ice Cube

The Threat: “Eazy E a’be hanging from a tree/With no Vaseline/Just a match and a little bit of gasoline”

You Should Fear For Your Life If: You still belong to NWA

Purpose of the Threat: Distinguish Ice Cube from his former group and legitimize his decision to go solo

In case you haven’t guessed, Ice Cube’s departure from NWA in the late 1980s was less than cordial. He was so angry that on his first solo album, AmeriKKKa’s Most Wanted, he dropped “No Vaseline,” which describes exactly how he was screwed out of the group, and how exactly he’s going to take his violent, graphic revenge. Even with the context of the feud, the lyrics are really lurid and shocking. It can be funny in a “I can’t believe he said that!” way, but especially now, it feels like a bit much.

When you think of Ice Cube now, you probably think of him as an actor first. His gun-toting NWA days and his nasty solo-artist days are virtually forgotten, and that makes the extremes of “No Vaseline” feel a little regretful. Ice Cube just doesn’t seem like the guy who would back up these threats anymore, and he also doesn’t feel like a guy who you’d want to see back up these threats anymore. This song is an interesting cultural moment, but it’s no longer effective.

“Monster” by Kanye West

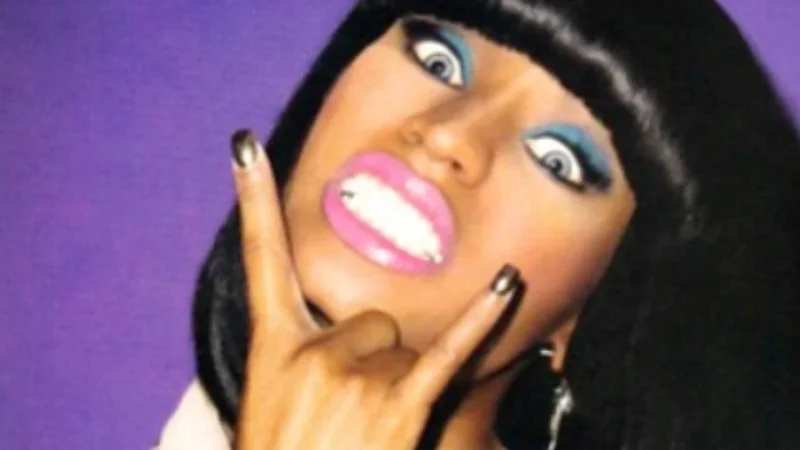

The Threat: Nicki Minaj says, “Ok, first thing’s first, I’ll eat your brains/Then Imma start rocking gold teeth and fangs”

You Should Be Afraid For Your Life If: you have a fear of monsters (obviously); you once doubted Nicki’s rapping proficiency

Purpose of the Threat: assert Nicki as a forceful emcee among some of the modern rap titans (and Rick Ross)

Listening to this song transports you to a moment when we all thought Nicki Minaj had a clear-cut path to the proverbial Hip Hop Hall of Fame. She showed up Kanye West, Jay-Z and Rick Ross all with one verse, and there was a hope that she would leverage this sudden ferocity into more immortal rap lines.

There’s a longer essay here asking why, but somehow, Nicki Minaj has never remotely sniffed the heights she reached on “Monster.” Nothing else in her catalog has lasted as long and nothing else is celebrated as much. It’s super strange, and while it doesn’t quite sap the viciousness clean out of this verse, it does color it with a small note of remorse. It’s immediately threatening, but it’s not threatening, and that’s because (like Ice Cube) the rest of the career doesn’t support it.

Weird—if you make a threat once, it feels like you’d have to be able to pass the idea that you can back it up forever. Is that unfair? Maybe.

“Senorita” by Vince Staples

The Threat: Vince Staples raps, “Baby either go hunt or be hunted/We crabs in a bucket, he called me a crab/So I shot him in front of the Douglas/I cannot be fucked with, we thuggin in public”

You Should Fear For Your Life If: you called Vince Staples a crab (I don’t know what this term means, but based on this song along, I assume it’s extremely disrespectful, because Vince killed the guy who said it)

Purpose of the Threat: convey a social reality

There’s a difference between direct-threat rap lyrics (like what we saw with NWA) and general-threat rap lyrics. Vince Staples dwells in general threats, because though what he says is never a direct threat to the listener, it still feels threatening. Staples’ rhymes are frank and casual and near-dismissive of their own horror, and that places him far outside the realm of the typical listener.

This is where our Serious Question becomes less “haha, remember when Ice Cube told Eazy E his penis was covered in MC Ren’s poop, implying that they were having anal sex?” and more “oh wait, there’s some intention and meaning behind what makes something threatening in hip hop.” This song is threatening because it’s foreign, but it’s also not hard to imagine it feeling threatening because it hits so close to home. Our next artist does this same thing.

“m.a.a.d city” by Kendrick Lamar

The Threat: “Picking up the fucking pump, picking off you suckers/Suck a dick or die or sucker punch, a wall of bullets coming from/AKs, ARs, ‘Aye y’all, duck!’”

You Should Fear For Your Life If: this is your Compton

Purpose of the Threat: convey a social reality; place Kendrick’s career within that reality

The most lyrically deft of our rap threats, Kendrick’s narration on “m.a.a.d city” paints a gory scene. It’s not funny. It’s not braggy. It’s real and matter-of-fact and it makes you feel very fortunate if you’re not party to the kinds of scenarios he describes in the song. On the other hand, the production in “m.a.a.d city” is one of the most party-ready beats on the album, and we’re back at the “In Da Club” paradox all over again.

What’s a little different here though is that when Kendrick discusses the violence he found in the streets of Compton, it isn’t to project some sort of image or persona (which, again, is how it feels when 50 Cent or Ice Cube or even NWA make threats in their music). Kendrick’s telling a story, and his imagery is here to inform, not intimidate. That doesn’t make this song feel any less threatening, but it does urge you to zoom out and think about things beyond your own life. That’s cool, and a little counter-intuitive when it comes to life-threatening lyrics.

“My Name Is” by Eminem

The Threat: “Well, since age 12 I felt like I’m someone else/Cause I hung my original self from the top bunk with a belt”

You Should Fear For Your Life If: you’re Eminem (and if you have kids)

Purpose of the Threat: to convey a personal reality

But what if the threatening persona you try to put forth as a rapper is damaging to yourself? That’s the curiosity surrounding Eminem’s Slim Shady arc, when he channeled all his juvenile rage into an alter-ego that, among other things, rapped about murdering his wife, assaulting celebrities, and exacting grisly vengeance on his negligent father.

Eminem never feels directly threatening. Like, you could probably take him in a fight if that’s how things went down, but that’s never been the point of his music. Two of the biggest conflicts of Eminem’s career come at the intersections of him and Slim Shady and him and his audience. Eminem was a threat to people because he was seen as a corrupting force of culture, and that corruption arrived in full on “My Name Is.” You knew from the first lyrics that this guy was going to be a problem: “Hi kids! Do you like violence?” It’s disturbing. Even worse is the follow-up. The little kid: “Yeah! Yeah! Yeah!”

“Run the Jewels” by Run the Jewels

he Threat: When El-P says, “I don’t wanna sound unkind but the sounds I make are the sounds of the hounds that are howling/Under your bed I’m here growling/Same time under the blanket you’re cowering”

The Second Threat: When Killer Mike says, “We the wolves that’s wilding/We often smile at sights of violence/Acting brave and courageous/Ain’t advantageous for health and safety”

You Should Fear For Your Life If: you oppose Run the Jewels and/or dope things

Purpose of the Threat: to solidify the arrival of a new influence in hip hop

If you go back up through this conversation, you’ll see that many of the tracks we examined—“M.E.T.H.O.D. Man,” “Straight Outta Compton,” “My Name Is”—are major-debut tracks. When hip hop artists make a debut, they’re defining who they are. Method Man told everyone he was a psycho. NWA told everyone they were rebels. Eminem told everyone he was sick. By naming their first song after themselves, Run the Jewels banked on their thesis statement being so overpowering and propulsive that it would become a sort of self-sufficient power source. No one legitimized either of these emcees; Killer Mike and El-P spoke for themselves, and then combined forces to speak for each other. By coming out on their opening record spraying bullets and gnashing teeth, they’re doing more than making a debut, they’re making victims. Here, look at this brag-lyric from Killer Mike:

“I’ll pull this pistol, put it on your poodle or your fuckin baby/She clutched the pearls, said ‘What in the world!’ and ‘I won’t give up shit!’/I pull the pistol on that poodle and I shot that bitch.”

First off, thank goodness Killer Mike didn’t murder the baby. Second off, as far as threats go, these are especially insane because by the time the song ends, you don’t need any more convincing that El-P and Killer Mike will mess your whole life up. The only reason that feeling lands is because they’re so singularly effective at making the threat—in other words, it’s because they’re so good at rapping. You don’t need evidence. You don’t need confirmation. You just want to back up.

“Gimme Da Loot” by Notorious B.I.G. vs. “Can’t C Me” by Tupac

Biggie’s Threat: “I’m dipping up the block and I’m robbing bitches too/Up the herringbones and bamboos/I wouldn’t give a fuck if you’re pregnant/Give me the baby rings and the #1 Mom pendant”

Pac’s Threat: “Must see my enemies defeated/I catch ‘em while they coked up and weeded/Open fire, now them niggas bleedin”

You Should Fear For Your Life If: you are a pregnant mother; you are coked up or weeded; you take a side in this feud

Purposes of these Threats: mythologize the emcee

While it’s contrived to pin these two against each other, threats from Biggie and Tupac serve the same purpose in regards to their wider careers and trajectories. Let’s look at them one at a time for a second:

Biggie’s story is all about inter-class mobility: He wants to go from the underclass of the streets to the upper class of celebrity, and most of his music explores the conflicts of that transition. “Gimme Da Loot” is about an older Biggie trying to teach a younger Biggie about survival via petty crime (sample line: “for the bread and butter I leave niggas in the gutter.”) On its album, Ready to Die, “Gimme Da Loot” presents the grungy contrast to the current Biggie’s luxurious surroundings. It helps us understand his path toward fame. It completes his origin story.

Tupac’s story, meanwhile, is all about intra-class mobility: He doesn’t want to leave the streets necessarily; he just wants to rule them. That’s why his lyrics in “Can’t C Me” are so bombastic and brash and front-facing—his dominion comes with being the alpha-dog. By bragging about murder, Tupac perpetuates the myth he’s trying to build around himself, and the very title of this song brings that home (In case you didn’t follow, Tupac’s enemies are blind because they’re dead. All dead people are blind, though not all blind people are dead. That’s important to remember).

So while the threats are on the surface quite similar—I’ll resort to violence to achieve what I want—the differing goals and narratives of Biggie and Tupac show that threats can effectively fuel mythmaking in hip hop. You don’t need to be a real murderer to be seen as legitimate. You just have to be consistent in the narrative you put forward. That’s why these rhymes work so well—we believe them because Biggie and Tupac have given us no choice but to believe them. There’s no alternative to their stories.

“Ruff Ryder’s Anthem” by DMX

The Threat: DMX screams, “Talk is cheap, motherfucker!” right after he fires a hail of bullets

You Should Fear For Your Life If: you’re in DMX’s line of fire (SPOILER ALERT: everyone is in DMX’s line of fire)

Purpose of the Threat: no frills about it; this is a warning

Here’s a true story from the peanut gallery: One time I was curious about DMX’s status in life (namely, if he was back in prison or not) so I googled him. Turns out, he was living in Phoenix, which is where I grew up. I found an approximate address, and it was actually about 15 minutes from my parents’ house. I called up my mom and asked her if the front door was locked. She said no and I said something like, “Mom, are you serious? DMX is loose in the area.” That’s when she hung up the phone. I think if my mom knew anything about DMX she would look back on that as an underreaction.

Any rapper is only as good as the threats they can legitimize, unless you’re DMX. He can legitimize any threat he ever makes, because DMX has been in on the action for some time now. Of course, his lyrical library is full of verbal threats, but this declarative at the end of “Ruff Ryders’ Anthem” is the most exemplary because instead of just running his mouth, he just goes ahead and guns down his opponents. Does it become more life-threatening than that?

By the way, as far as the listener is concerned, are we sure no one actually died during the making of “Ruff Ryders’ Anthem?” Sometimes, threats are threats, and when it comes to DMX, it’s best to just take his word for it.

***

Whether it’s gunfire of a real nature or gunfire of a verbal nature, life-threatening moments in rap are as diverse as the emcees who deliver them. Run the Jewels’ threats tell you to clear the runway for their own personal landing. Wu Tang Clan’s threats affirm their collective mission and unity. Eminem’s threats tell you not to come any closer, lest he hurt himself. The function is wide-ranging and different, but there’s a common thread: purpose.

True, some of these barbs feel authentic and some don’t. Some emerge from experience and some from fantasy. Some solidify collectives while others bolster personal reputations or myths. There’s something to be said here for the fact that violent and angry rap lyrics somehow can do more than just shock the listener. They can make you think as much as they can make you duck for cover.

For all its self-inflation and idolization, threats in rap somehow make us feel closer to the emcee. For a moment, we’re transported and involved. There’s a thrill here, a vicarious power that, though always secondhand, will never diminish in returns. After all, the real rush doesn’t come from being part of the action, it comes from feeling like you went through something horrible, and you survived.